A Comprehensive Introduction To Investing In Stocks

Investing in stocks is commonly associated with building wealth. Many people get excited by this idea, but then are overwhelmed on how to get started.

This guide is long, but it will explain how the stock market works and some of the factors to think about when investing. You should be ready to do your own research and buy your first stock after finishing!

What Are Stocks?

Stocks represent who owns a company. A company’s stock can be any number of shares. It could be a million shares or a billion shares. Each company has decided to divide their company into different sized portions.

The amount of ownership a single share is worth depends on the total number of shares.

Coca Cola has over 4 billion shares, so each share is worth less than 0.00000000025% of the company.

Dividing a company this way provides flexibility for people to purchase as much ownership in a company as they would like.

Why Would A Company Sell Shares?

So why would any owner of a company be willing to sell ownership of their company? If you owned 10% of a billion dollar company, you would be worth 100 million dollars. But if you owned 100% of that company, you would be worth a billion dollars!

There are many reasons to sell ownership in a company. We only need to understand one to realize why the stock market exists.

Many businesses end up in a position where if they had more money, they could grow much faster. Let’s say you had a company that was worth 20 million dollars. You own 100% of it so your net worth is 20 million dollars.

There are enough opportunities for your business where your company could easily be worth a billion dollars, but you need another 20 million in cash to make the necessary investments. It could be R&D, being able to manufacture items in larger quantities, building new stores/locations, or hiring more sales people.

One option is going to the bank and asking for a loan. However, banks expect loans to be paid regardless of whether your investments work out or not. You may also need a few months or a couple of years before your investments bear fruit, but banks expect you to start paying back the loan immediately.

The challenge here is that if your investments don’t work out or take longer to pay off than you expect, you will still be expected to pay the bank. The risk is all on your company.

By selling part of your company, you are asking someone to share some of that risk. If the company fails, you all fail. If the company succeeds, you all succeed. Shareholders don’t demand monthly payments like banks do.

So let’s say you offer to sell 50% of your company for that 20 million dollars. You make the necessary investments and the company is soon worth 1 billion dollars. With your 50%, your net worth is now 500 million dollars.

If you hadn’t sold shares in your company, you wouldn’t have had the capital to make those investments. Your company would grow slower, let’s say to 100 million dollars. That’s still a lot of money, but a lot less than you would have if you had sold part of your company.

You may be asking yourself “wait a minute, if 100% of my company is worth 20 million dollars, how could I sell half of it for 20 million dollars? Shouldn’t people want to pay me 10 million for 50% of my company instead?”

To answer that, we should talk a bit about stock prices.

How Do Stock Prices work?

A stock is worth as much as someone is willing to buy it for and someone else is willing to sell it for. When we said earlier that you had a company “worth 20 million”, that statement is kind of fuzzy. It’s only worth 20 million if you are willing to sell it at 20 million and others are willing to buy it at 20 million.

Consequently, you could convince potential investors that if they are willing to give you 20 million dollars for 50% of the company, you will turn that into 500 million dollars within a few years. That’s a great rate of return for those investors. Investors are not valuing your business based on how much money it makes today. They are valuing it based on how much they expect it to make tomorrow.

So while your company may only be worth 20 million dollars today, those investors may choose to value your company at 40 million dollars on the presumption that you will turn the whole company into a 1 billion dollar company and give those investors a $500 million dollar return.

Determining how much a company will grow in the future is a complicated affair. There are an overwhelming number of factors to take into account. We will go into some of these factors later. For now, it is important to note that different people will have different predictions for how much a company will grow. That means they will all be willing to pay a different amount for that company.

This can get tricky when there are thousands, or even millions, of people all with a different idea of what the price of a company’s stock should be. A stock exchange helps coordinate all these potential buyers and sellers of that stock.

The way it works is that a number of people who own shares in a company will post how many shares they are willing to sell and the price they want to sell those shares at.

For example:

- Joe is willing to sell 100 shares at $50

- Mary is willing to sell 700 shares at $49

- Shinzo is willing to sell 100 shares at $48

Another group of people will post how many shares they are willing to buy and the price they want to buy those shares at:

- Luke is willing to buy 100 shares at $47

- Elizabeth is willing to buy 300 shares at $46

- Scarlett is willing to buy 500 shares at $45

No trade happens here since the highest price someone is willing to pay is $47 and the lowest price someone is willing to sell is $48. This difference is called the bid-ask spread.

Now let’s say Luke is willing to go up to $48. Suddenly, someone is willing to buy and someone is willing to sell at the same price. A market maker at a stock exchange such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or the NASDAQ will handle the trade.

Since Luke has just purchased 100 shares from Shinzo, they are no longer listed as willing to buy or sell shares. We are left with Mary willing to sell at $49 and Elizabeth willing to buy at $46. This is our new bid-ask spread.

We are also left with a stock price of $48. Whenever anyone talks about a stock price, they are really talking about the price that was agreed upon by two parties in the last trade.

That price is then multiplied by the number of shares to determine the market capitalization (or market cap) for the company. The number of shares in that last trade does not matter. Market cap is determined only by the price and the total number of shares.

Let’s use Coca Cola as another example. At the beginning of 2020, Coca Cola has 4.3 billion shares. Say the last trade was at $55. That makes the market cap of Coca Cola 236 billion dollars. The number of shares in that last trade does not matter. Market cap is determined only by the price and the total number of shares.

Consequently, it is important to note here that the share price isn’t the reflection of a company’s value. A company could have a stock price of $100 per share, but that does not necessarily mean that investor think that company is worth more than Coca Cola. The total number of shares need to be accounted for to know what investors are valuing a company at.

Market cap is not perfect however. Look at the Coca Cola example closer. A trade of 1000 shares determined the market cap for a company with 4.3 billion shares. The market cap of the whole company was determined by exchanging ownership of 0.00000023% of the shares.

If the next trade of Coca Cola was at $50 for 1000 shares, the stock price would be $50. The market cap of Coca Cola would now be 215 billion dollars. That’s a 21 billion dollar drop in market cap over a trade valued at 50 thousand dollars.

Consequently, if the next trade was at $25 dollars for 1000 shares, the market cap would drop another 112 billion dollars based on a trade valued at 25 thousand dollars.

And that trade is determined by the opinion of two people. It ignores millions of other shareholders who would refuse to sell at that price and millions of other investors who would refuse to buy at that price. Unfortunately, it is hard to put a price on the disagreement between millions of people (or even a few thousand). There are simply too many data points to account for.

Using the price on the last trade is the best approximation we can get for the value of a company.

The number of people willing to buy and sell shares in stock also creates some sense of stability. A company like Coca Cola sees around 10 million shares exchange hands on a daily basis. Many individual trades are happening every second so no one trade affects the price for long.

There is also the fact that the way people list their intention to buy or sell shares will usually limit how far the price in one trade will be from the next trade. If someone is willing to sell their shares for $25, but sees that someone is willing to buy for $47, they would sell their shares for $47 instead of $25.

This does not mean it is impossible for everyone to change their mind at the same time! You will find that there is always a number of companies somewhere that have had a big jump or a big fall in their stock price.

By now you may be wondering what would cause a stock price to move. Why is Coca Cola worth over 200 billion dollars instead of 100 billion dollars? Why doesn’t the price jump back and forth constantly? What could cause it to go up significantly or go down significantly?

To answer these questions, we will have to start talking about how investors value companies.

How Do We Value A Company?

While there are a ton of factors that go into determining the value of a business, most of them can be grouped into a handful of buckets. We’ll go through some of the more important factors in each bucket to help you get an idea of where to start when you go to learn more.

The Fundamentals

The first group are the fundamentals of a business. These are the financial numbers related to the business such as revenue. Companies on stock exchanges are considered “public companies” and are required to give everyone these numbers 4 times a year in quarterly and annual reports.

An example of what part of these reports look like:

This is Microsoft’s quarterly report for the 4th quarter of 2019.

This is Microsoft’s quarterly report for the 4th quarter of 2019.

Understanding why these numbers are important is fairly straightforward. We value businesses based on their ability to make money and revenue represents how much money a business brings in.

Naturally we also have to start thinking about how much money a company spent to earn that revenue. How much was spent on employee or executive salaries? How much was spent on advertising? How much was spent on raw materials? How much was spent on rent? And of course, how much was paid in taxes?

The money that is left is called net income or earnings. This leads into a metric that you will most likely here a lot: the price/earnings ratio

This essentially divides the price of a stock by the earnings per share. Earnings per share is the total earnings a company made in the past year divided by the number of shares. We can also divide the market cap of a company by the total earnings from the past year and get the same ratio.

Most places where you can look up a stock will display the P/E ratio. This is a stock summary from TD Ameritrade:

The P/E ratio essentially tells us how many years it would take for the company to essentially earn its market cap. A P/E ratio of 7 means a company would take 7 years to earn the same amount of money as its market cap. A P/E ratio of 15 means it would take 15 years. We’ll dig into why different companies have different ratios later.

Using earnings in this calculation is often more appropriate than revenue. Let’s say Company ABC makes 1 billion dollars in revenue and earns 100 million from it. Company EFG makes 500 million dollars in revenue and also earns 100 million dollars.

Company ABC has double the revenue of Company EFG, but both companies earn the same amount. They essentially get to put the same amount of money in the bank. That provides an argument that both companies are worth the same price even though one company takes in more revenue.

What does a company do with this money in the bank? There are a number of options.

The money could be invested in the business to find more ways to grow revenue. The may include research & development, hiring more workers, buying other companies, etc. The goal here is to spend the money today in order to make a lot more money in the future. It is similar to what a business would do with the money from selling stock in the first place.

A company could also give the money to shareholders. Many investors are happy with this move since they can get money from their investment without selling any of their shares. This often happens in the form of a “dividend”. Dividends are usually paid out once a quarter (4 times a year). When you see the dividend yield mentioned about a stock, it represents the percentage of a company’s stock price that is paid out every year. For example: if you invested in a stock with a 5% yield, you would get 1.25% of the stock price back every 3 months.

Since dividends are paid 4 times a year and stock prices change many times a second, the dividend yield often changes. If you buy a stock at $100 a share with a $5 a year dividend, it will have a yield of 5%. If the stock goes down to $50 a share, the dividend yield is now 10% because the dividend is still $5. Note that dividend payments can and do change, just not as quickly as stock prices.

Extra money can also be used to buy back stock. Let’s say Company XYZ has 1 billion shares and each share is worth 10 dollars. The market cap of the company is 10 billion dollars. Company XYZ also has a lot of money in the bank and decides they will use 250 million dollars to buy back stock.

At 10 dollars a share, they would be purchasing 25 million shares. That would reduce the total number of shares in Company XYZ to be 975 million. Assuming all investors believed Company XYZ would be worth a market cap of 10 billion dollars, the price of each share would then go up to $10.25. If you owned 100 shares, they value of those shares would go up from $1000 to $1025.

This is a little more roundabout way of giving money back to shareholders than paying a dividend, but it theoretically serves the same purpose. We won’t go too much into why the math never works out this cleanly, but there will be links in the reading list that point to articles which will.

Companies do not have to invest their money or give it back to shareholders. They can choose to keep the money sitting in the bank. This leads us into another important metric: book value otherwise known as stockholder’s equity

The easiest way to think about book value is “what would the company be worth if we stopped doing business today and sold everything the company owned?”

That means counting up all the money a company has in the bank, all it’s assets such as land or equipment, all the money it is owed, etc. These are a company’s assets. You subtract the company’s liabilities such as debt from those assets and you are left with the company’s book value.

Here is what the numbers look like in Microsoft’s quarterly report:

While this is the easiest way to think about book value, there are some nuances involved. For example, you may be able to buy a piece of factory equipment for $500k, but if you wouldn’t get close to that much if you had to sell it.

There are also intangible assets such as brand. For example, the name Apple or Google or Netflix is worth something. Company’s do have to make some effort to trying to put a value on these types of assets, but as you can guess there is a lot of subjectivity involved in how much something like a brand is worth. Yet, you will still see an exact value listed in a quarterly report.

Saying that these exact values are an accurate representation of the value of intangibles such as brand is the same as saying the market cap is an accurate representation of the value of a company. There’s many different opinions, but we have settled on an approximation. The actual value could be very different.

For these reasons, you should not automatically assume that a company with a book value greater than the market cap is a good investment. It may be tempting to view a company with $5 billion in book value and a $1 billion market cap as buying $5 for $1. It seems like that’s an opportunity for easy money.

However, every other investor has access to the same information you do. If you see a situation like this, it is likely that many investors believe the company will start losing massive amounts of money or go bankrupt. They also suspect that the assets are worth less than stated in the quarterly report, or the company’s management will start taking on more debt to keep the company afloat. That future debt will lower the book value of the company.

While we have simplified much of the discussion around metrics, this should have given you a good overview of some of the number you’re looking at when evaluating a stock. There are many other metrics to consider. More importantly, each metric can be manipulated to make a company look better than it is. There will be several sources in the reading list section where you can learn more about these topics.

For now, we’ll just note that while metrics are important, you can’t solely rely on the numbers when valuing a business. A company with a market cap of $2 billion dollars, with $2 billion dollars in book value, and a P/E ratio of 5 would look amazing at first.

However, if this company’s only product was making beepers

…and the CEO publicly stated that beepers was the only thing the company would make because beepers are the future

…and it was the early 2000s

…then this company would start to look like a poor investment.

While there are some professions that still can justify the use of beepers, they’re not exactly common today. Even a flipphone has more utility to the average person than a beeper. This is not the kind of product that will make a company a lot of money and consequently not a great investment.

That leads us into our next set of factors for valuing a business.

The Business

Thinking about what a company actually does to make money sounds obvious. Being able to make a good evaluation of a business is extremely difficult however.

The decline of beepers seems obvious to us now. But was it really that obvious back then? If your answer is yes, then let me ask you: why are people still using beepers today? What is the value beepers provide over smartphones?

Why Are Pagers Still A Thing? on Vice

Why Are Pagers Still A Thing? on Vice

Understanding that value is critical in providing insights into what the existing market potential of beepers are and why they didn’t just disappear instantly. It also allows us to determine whether the market is growing or shrinking and how quickly it is moving in either direction.

Let’s look at smartphones as our next example. One of the dominant players in the smartphone market is Apple. When the first iPhone came out in 2007, Apple’s market cap was approximately $110 billion. At the end of 2019, it was over $1.3 trillion. If you invested in 2007, you would have made 10 times the money you put in over the course of 12 years.

Many investments like Apple seem like a slam dunk when you look in the past. However, when you make an investment today you don’t get to see the future before making that investment. The information you have is imperfect and your decisions will most likely be imperfect as well. No one can predict the future perfectly.

Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple and an early investor in Pixar, famously sold nearly all his Apple stock in 1997. In 2003, he assumed Apple’s stock wasn’t going to do that well and traded his 40 million stock options for 10 million shares. By 2010, that ended up being a decision that cost 10 billion dollars.

Here we have one of the greatest businessmen in modern history underestimating the performance of a company he was running. It would be asinine to claim that Steve Jobs wasn’t smart. This simply shows how difficult it is to determine how well a company’s business will do and how the stock price will react in the future.

While there are no shortage of business books writing about how Apple’s rise was so obvious, they all have the benefit of hindsight. In the late 90s, Apple was close to bankrupt. Microsoft had market dominance. It would have been hard to make a case that iMacs could carve out enough of a niche to bring the company to success. Fortunately for Apple, consumers loved the product.

iPhones easily become Apple’s biggest winner in the 2010s. Was it that obvious when they first came out in 2007 though? Smartphones had existed years before the iPhone. Lots of people had Blackberry devices. What was actually better about the iPhone at the time?

Smartphones at the time were also owned by those using them for work. It made sense because they were expensive and required a more expensive service plan. Yet, something about the iPhone made consumers willing to bear those extra costs.

Also, what was going to happen to the leading smartphone maker at the time? Blackberry had a product that millions of people were using for years. Was the introduction of the iPhone going to make Blackberry phones obsolete? What were even the differences between an iPhone and a Blackberry phone? Did those differences matter?

More importantly, was one of those companies going to dominate the smartphone market or was there room for both Apple and Blackberry?

It is easy to look back and answer all those questions. It is much harder to be able to answer those questions at the time when it mattered. Being able to determine that the iPhone was going to be a big win for Apple and a big loss for Blackberry required a strong understanding of what a good product is and what consumers as a whole want. After all, today we know there was room for more than one smartphone manufacturer. There just wasn’t room for Blackberry.

Developing a strong understanding of what good products are is not easy. If this was easy, there would be thousands of companies like Apple rather than just a handful.

by market cap in March 2020

If this was easy, it would also be harder for you to make money in the stock market. Remember how stock prices work? We have a list of potential buyers and potential sellers.

If more people believe that a company is going to do well, then the people selling are going to ask for a higher price and the people buying are willing to pay a higher price. This will result in a higher P/E ratio for a company.

Remember that a P/E ratio of 15 means the company will take 15 years to earn its market cap assuming zero growth.

If people believe a company will grow very fast, and take less time to earn the current market cap, then the demand for that company’s stock will increase. The stock price will go up, but so will the P/E ratio. That P/E ratio’s only limit is the will of people to keep buying that stock. It is not unusual to see P/E ratios of 100 or up.

A P/E ratio of 100 means a company needs 100 years to earn its market cap assuming zero growth. No one wants to wait that long. The assumption is that the growth will be very high, say a 50% increase in revenue/earnings year after year.

The question becomes whether a company can meet those high expectations from investors. Let’s look at Microsoft as an example. Microsoft is a great business. It is one of the largest companies in the world with both great products and dominance in certain areas. If you invested in Microsoft in the 1980s or early 1990s, you probably did very well.

Microsoft price history 1986-2020

Microsoft price history 1986-2020

This did require you to believe in a market of personal computers. It seems obvious today when everyone walks around with a more powerful computer than anything they had in the 1980s, but back then it was not that obvious.

What would people do with computers? How could they afford computers? Many people back then didn’t think it would be that big of a market and they were very very wrong. Microsoft grew quite fast.

However, people started looking at Microsoft’s fast growth and assumed it could keep it up or grow even faster. More and more people started buying Microsoft stock. The P/E ratio hit 50 in 1999 at the height of the dot com bubble. The expectations were high. And then the stock price dropped by 50% in 2001.

Microsoft price history 2000-2001

Microsoft price history 2000-2001

Microsoft was still a good business when the stock price dropped. But the frenzy of people buying Microsoft stock had made the stock a bad investment. The expectations were too high for even Microsoft to meet. When those hopes were dashed, so was the stock price.

Unfortunately, you would not have done well if you invested in Microsoft in 1999 / 2000. The value of that investment would have been cut in half by 2001. The stock price would not reach that level again until 2016. Your investment would have take 15 years to break even!

Microsoft price history 2001-2016

Microsoft price history 2001-2016

There were many other companies with high expectations in 1999. That leads us into our next set of factors which influence the stock price.

The Narrative

The narrative about a company is a huge contributor to the current stock price. Regardless of what the fundamentals or the business model of a company is, if the narrative is good then the stock price will be high. If the narrative is bad, then the stock price will be low.

We talked about how the expectations, which are caused by the narrative, of Microsoft became so high that it couldn’t meet them despite being a great business.

During the dot com bubble, there were plenty of companies with poor businesses and poor fundamentals that also had high stock prices. The internet was fairly new at that time and everyone assumed correctly that it was a world changing technology.

However, they assumed incorrectly that every “internet company” had a good business model.

The result was that many of the companies that were making money had P/Es so high that they could not meet those expectations. Other companies had market caps in the hundreds of millions or billions of dollars despite very little revenue and heavy losses (negative earnings).

There was an expectation that many of these businesses would get large very quickly. We look at how prevalent e-commerce is today and can’t even imagine the industry not doing well. People in 1999 also thought e-commerce was going to be big. The problem was how long it would actually take. The reality was good, but couldn’t meet the expectation.

Not only that, many e-commerce companies during the dot com bubble were incapable of making a profit. It doesn’t matter if you can double your revenues every year if you lose money on every sale. You would just be losing twice as much money!

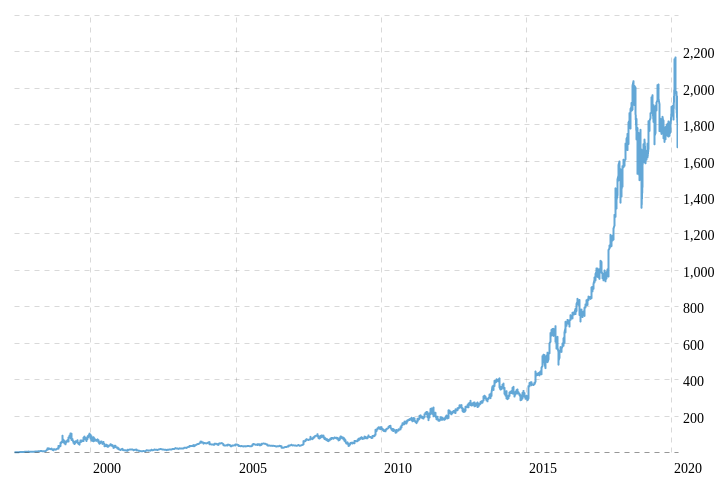

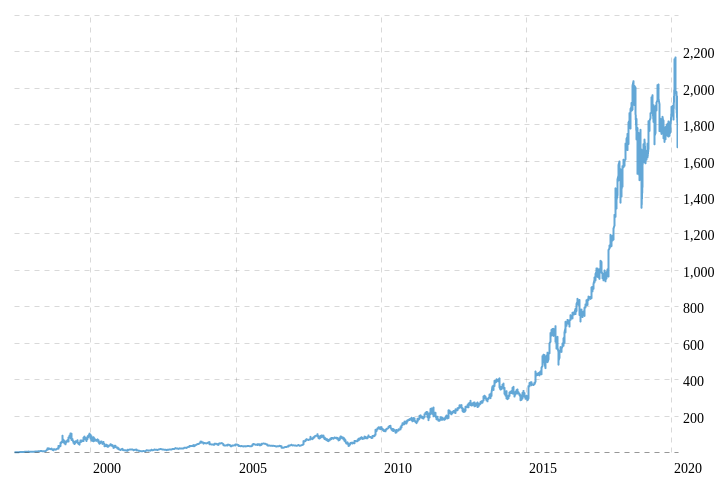

There are of course situations where a positive narrative is correct and justifies a high P/E ratio. Look at Amazon. The stock has rarely had a P/E of less than 50 in its entire history. Oftentimes, the P/E has been in the hundreds or non-existent in the years Amazon lost money. Yet there is no denying that anyone who invested in Amazon before 2017 is extremely happy with their investment.

Amazon price history 1997-2020

Amazon price history 1997-2020

Even if you invested in Amazon at the height of the dot com bubble, you would have had a return of 20x-40x at the beginning of 2020. That’s a pretty good return over 20 years.

With the exception of the dot com bubble popping, the narrative around Amazon has always been good and it has been justified so far. Whether it can maintain that narrative for the next 20 years remains to be seen.

Narrative can also keep a company’s stock price down even while they are growing. There are no shortage of companies whose stock price has gone down even though their earnings have gone up. It’s because investors believe their growth will stop. The company has failed to convince them that they can keep going.

Whether investors are right or not is always an interesting question. Investors as a whole can be right about some stocks while wrong about others. Amazon is an example of them being right so far. Most other internet companies in 1999 are examples of investors being too optimistic. Then there is AMD, which is an example of them being overly negative.

In 2015, almost everyone thought AMD was going bankrupt. Their market share was puny compared to Intel’s. Their fundamentals were terrible since they had a lot of debt. Their R&D budget was 3 billion dollars compared to Intel’s 30 billion dollars, bringing doubts that they could actually make better products. All the numbers looked bad and that created a horrific narrative for the company that showed in the stock price.

Investors as a whole were wrong in this case. Despite having only 10% of the R&D budget of their larger competitor, AMD managed to build great products. At the beginning of 2020, they had been selling 7nm chips (an important milestone in building CPUs) for a couple of years while Intel can’t do the same until 2021.

The narrative around AMD has obviously changed. Someone who invested in AMD in 2015 would have made 20x their investment if they sold at the beginning of 2020. It is too soon to tell whether this new narrative has overreacted in being too optimistic about AMD’s future prospects.

It can be a little overwhelming trying to account for all these factors when evaluating a stock. Let’s try to sum things up a little.

Picking Stocks

It is probably easiest to think things in these terms:

- The Fundamentals show how a company has done in the past

- The Business shows what a company’s prospects are in the future

- The Narrative shows what investors think the current stock price should be

This is an oversimplification of these factors, but thinking in this way will serve as a foundation for you to learn more later.

The most tempting way to invest is to look at the current narrative around a company and follow suit. This strategy would have worked very well with Amazon.

Amazon price history 1997-2020

Amazon price history 1997-2020

However, it is fairly rare for a company to have a consistent narrative over many years like Amazon. Most companies have their narratives change as their business and fundamentals change. Sometimes this is positive like with AMD. Many times it is also negative.

And when a narrative goes negative, it can be very sudden. Stock prices don’t necessarily move slowly 1-2% at a time. They can go up or down by 10%, 20%, 50%, etc. They can do this instantly. Remember that stock prices are determined when people agree on a price.

Everyone can all of a sudden agree on a new price that is much higher or lower than the old one. We mentioned earlier that the high volume of trades in companies like Coca Cola can create some sense of stability. This may be true most of the time, but that does not make a dramatic change in stock price impossible.

You may have heard the common trope of “buy low, sell high”. It’s obvious that doing this will make you money.

When you follow the narrative, you end up buying when the narrative is good and selling when the narrative goes bad. That creates a situation where you buy high and sell low.

You could of course buy as a stock is going up and sell just when it starts to go down.

But doing this involves no small amount of luck. You won’t necessarily know when the narrative will change.

The most profitable way to invest is to buy stocks when you believe a negative narrative is wrong. This is challenging. It isn’t as simple as buying a stock when it goes down because that stock could go down for a very good reason and it can stay down for years. It may even go bankrupt at which point you have lost most of your investment.

Buying a stock when you believe the narrative is wrong requires you to have a very strong understanding of the company’s business. This usually means having a stronger understanding than most other investors.

This is an extremely easy concept to grasp, but hard to do. There are no quick tips or easy shortcuts here. You have to do the work to learn as much as possible about a business.

Funds

A common alternative to picking individual stocks is to invest in mutual funds or index funds.

Funds are groups of stocks that you buy together. For example, you may buy Mutual Fund ABC and it will consist of 20 stocks. The price of shares in Mutual Fund ABC depends on the prices of all 20 stocks in that fund.

Mutual funds are actively managed. That means there is a person or a team of people who are picking the individual stocks for that fund. This requires a lot of work and comes at the cost of an annual fee that is called the “expense ratio”. A typical mutual fund may charge you an expense ratio of 1-2%. This is of ALL the money you invest in that fund regardless of whether they make you money or not.

Index funds are passively managed. You may have heard of the S&P 500, the Dow Jones Industrial, or the NASDAQ Composite.

These indices are groups of stocks created by their respective organizations to attempt to represent the performance of the overall stock market without necessarily including every stock that exists. An index fund is created to mirror the prices of these indices.

Comparing an index fund with the index

Comparing an index fund with the index

Since the stocks in index funds are picked automatically, there is a lot less effort spent in managing them. The expense ratio of an index fund will be closer to 0.1-0.2%. That makes them significantly cheaper than a mutual fund.

Lots of research has been done on how the performance of mutual funds is not much better than index funds. However, there are undoubtedly some mutual fund managers who are legitimately good and can outperform index funds reliably. Being able to tell who these managers are will require you to understand how to pick stocks yourself. Only then can you properly evaluate a manager’s ability to pick stocks.

Passive funds are the easiest way to get started in investing. Many others would recommend starting with an index fund that follows the S&P 500 such as the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF or the Fidelity 500.

Making Your First Investment

Making your first investment in fairly straightforward. There are a number of online brokerages that can be found easily with a quick search.

Some search results for online brokers

There are indeed a lot of options, though they tend to offer the same services. It is hard to go wrong with any of the bigger and more popular services. You should be able to sign up for an account with several of them and choose one that you feel is easiest to use.

Each broker has their own interface. However, their business is to let you buy and sell stocks. They should have an easy way for you to search for either the name of a company or their stock ticker. For example: Amazon’s stock ticker in NASDAQ: AMZN. You should be able to find Amazon’s stock by searching for Amazon or AMZN.

Once you add funds to your brokerage account, you should be able to buy and sell stocks. Note that trades only occur when the stock exchanges are open. This is 9:30 am to 4 pm Eastern time. You can put in your stock order at any time, but they only complete during trading hours.

There are lots of different types of trades, but the most common ones for those new to investing are market orders and limit orders.

Market orders are simple. You request to buy or sell at whatever price is available.

Limit orders allow you to set a price limit. For example: a limit order of $45 to buy company ABC’s stock will execute if the stock price is $45 or less.

If the price goes above $45, then the order will wait until the stock price drops below $45 or it expires (which may be end of day by default).

Consequently, if you already own shares of company ABC, a limit order of $50 to sell company ABC’s stock will execute if the stock price is $50 or more.

Once you put in an order and it executes, you will be the owner of a company’s stock. You are now invested in the stock market!

When Is A Good Time To Start?

You may have some anxiety of when to start. Buying when the stock market is at a high is a legitimate worry. How do you know if you’re in a bubble like the dot com bubble or if the market is going up for good reason?

There is a concept called dollar cost averaging that may help.

The way it works is you invest an small amount of money every period of time. It could be weekly, or it could be monthly, or bi-monthly. The goal is to make it frequent and consistent.

The result is that you will invest when the market is at a high, but you will also invest when it is at a low.

Diversifying over time like this is an admission that you do not know when the overall market will go up or down. However, by making periodic investments in all conditions, the money you make from the market lows will more than likely make up for any investments you made during market highs.

Let’s say you started in December 2006. You commit to putting $1000 every month in a S&P 500 index fund. By February 2009, you would have put in $27,000. Your portfolio would be worth $15,832 due to starting your investment at a market high and going through a market crash. You feel bad.

But you presevere. You don’t think society is going to fall apart. You keep putting in $1000 every month. By December 2010, you would have put in $49,000. Your portfolio is worth $53,415.

The market hasn’t even fully recovered from the crash. The high of the S&P 500 was $1549 during 2007. It is only $1257 in 2010. But because you also chose to invest while the market was down, those investments helped average out the investments you made when the market was high and you still end up with a small profit.

In March 2013, the S&P 500 passed its 2007 high to be $1569. If you had continued to dollar cost average your investments, you would have put in a total of $76,000. Your portfolio would be worth $98,094.

The market pretty much just keeps going up from there until the coranavirus pandemic hits in 2020. It is up to you to decide the best course of action at this point.

Now, could you have made more money if you could time the markets? Sure! That involves a great amount of both skill and luck however. It is also an intimidating task if you are just learning about the stock market.

If you can keep a time horizon of many years, then dollar cost averaging on an index fund can provide you with moderate profits at a minimal amount of effort. It also means that you can start investing at any time.

Parting Thoughts

We hope this article gave you a good understanding of how the stock market works. There is definitely a lot more to learn in order to be successful.

There is also the potential to lose some of your hard earned money. That can be scary. What we will say is this: you don’t actually lose any money until you choose to sell a stock for less than you bought it.

Look at the example earlier with dollar cost averaging. The value of your portfolio goes down significantly in 2009. But you don’t actually lose any money unless you sold stocks in 2009. Good businesses will often have their stock prices recover. There’s a profit for you if they do.

Investing in stocks is not only a great way to build wealth, but it can be fun and interesting too. We hope you enjoy the experience. Good luck!

We need to have a disclaimer here to specify that we are not responsible for any investment decisions you choose to make.

DISCLAIMER: Dynomantle Technologies LLC is not a registered investment, legal, or tax advisor or a broker/dealer. The information presented in this article is meant for educational purposes and is not intended as, and shall not be understood or construed as, financial advice.

The authors may own positions in one or all of the stocks mentioned.

Reading List

While this article serves to provide a comprehensive introduction to investing in stocks, it is by no means a complete guide.

Here are some excellent resources for learning more.

General Knowledge

Stock Ideas

Index Funds

Acknowledgements

We thank unDraw for a number of graphics that we used.

We also thank TD Ameritrade, macrotrends, and Google for providing many of the charts we used.

Article on Marketwatch

Article on Marketwatch

AMD price history 2012-2015

AMD price history 2012-2015 AMD price history 2012-2020

AMD price history 2012-2020